Education

Speech or profile paper about mounds

What are mounds?

Terps (or mounds) are elevated dwelling places in an area that is regularly flooded. The largest group of mounds in the Netherlands was built between 600 BC. and 1100 AD raised in the north of the provinces of Friesland and Groningen. These areas had not yet been diked. They were vastsalt marshes, intersected by bowers. The people built mounds of sod and manure on the somewhat higher places on the salt marsh. They had large houses with built-in stables, they kept livestock and they grew all kinds of crops. The seawater flowed into the bowers when the tide was very high and then flooded parts of the salt marshes. New fertile clay was deposited. This was favorable for arable farming and livestock farming. People also collected wild plants and molluscs, fished, caught birds, and occasionally hunted. But livestock was more important to them than fishing and hunting.

Occupation phases within the Frisian and Groningen mounds

Archeology distinguishes different phases of occupation. Each phase has its own material culture, such as house building, pottery, metal objects (see Image bank). The following, partially overlapping periods of occupation are distinguished in the mounds and mounds area of Friesland and Groningen:

late Middle Ages (1000 to 1500 AD).

Terps were also built in undiked areas in North Holland, near Schagen. This happened in the early Middle Ages. On Kampereiland, near Kampen, farms were built on mounds in the late Middle Ages. And along the major rivers the farms are often located on an elevation, a mound.

The mound landscape between 800 and 900 AD.

This is a digital 3D reconstruction (illustration) of the mound landscape made by the biologist Ulco Glimmerveen. The drawing gives an impression of the mound area in the 9th century AD. Are you a student or are you working on an assignment about mounds? Then you may use this drawing, stating the source: illustrator Ulco Glimmerveen, downloaded from https://www.terpenonderzoek.nl/onderwijs/. The illustrations may not be used in printing or other publications.

Door te klikken op de illustratie, wordt er een grotere versie getoond. With your right mouse button you can save it and use it in your work. Details of the artwork can be found via these links:

- detail: mound village

- detail: creeks, arbors and ditches

- detail: mound village with a simple church

Mound village

Terp village This part of the illustration by Ulco Glimmerveen shows a fairly large terp village with a number of farms. Some residential buildings were large, up to 30 meters long; others were shorter. The houses had no windows. There were also barns for additional stable and storage space. The farm itself also had room for livestock: cattle, sheep, horses and a few pigs. Because people and livestock lived under the same roof, these farms were called stable houses. In the illustration, a new house is just being built. The walls are made of stacked turf, which was laid on the salt marsh. At the top of this illustration, two men are cutting sod. An arch-shaped roof construction was made with wood, which was valuable in the terpen area. Wood was often used from discarded or stranded ships. Then the roof was covered with sod, grasses or straw. At the Yeb Hettinga Museum in Firdgum (Fr.) there is a replica sod house from about 700 AD. You can also view this from the inside.

Cooking and heating was mainly done with dried manure. Here and there you will see rectangular or round manure mounds. In the middle of the mound village you will see a large dug pit in which rainwater was collected. When the salt marsh was flooded with salt water, the cattle could drink here. Fresh water is especially important for dairy cows. The drinking water for the people came from square, dug wells: you see four of them. One of the wells has a well gallows, a construction for lowering a bucket into the well and raising it again filled with water.

A flock of sheep with their shepherd and dog have just returned to the mound. Cows pull wagons with hay. The sheep in these illustrations are colored white and the cattle dark brown. But we don't actually know what color the cattle were. Many cattle bones are recovered. But you cannot directly read the color of the coat from that. Under two shelters there are merchandise, mainly earthenware pots. The terp inhabitants made earthenware pots themselves, but also imported them, including from Walberberg, Badorf and Mayen, all in contemporary Germany (information Angelique Kaspers MA, GIA/RUG).

Sheepskins hang to dry. The people wore woolen or linen clothes, in beautiful colors. The wool came from our own sheep. The linen comes from home-grown flax. Many spinstones (made of pottery, bone and antler) and weaving weights are found in mounds. The wool and flax were spun and woven themselves. Wool was also sold as a commodity. Frisian cloth was known far and wide. Arable farming produced more than enough products for the country's own needs. Yet the impression is that mainly livestock products, such as hides, wool and perhaps cheese, were traded. The round object with a hole on the right is an iron smelting furnace: the residents made their own iron objects.

There are three boats in the harbor next to the village. The little ones were used for fishing, delivering or picking up goods in the neighborhood, and making visits. The larger boat, with a sail, was used to cover greater distances. The terpen area was part of trade networks throughout the North Sea region and far beyond. All kinds of merchandise, including wine, will have been delivered in the barrels.

There are blue rags hanging at the back house. These have just been dyed with the blue dye that is extracted from the woad plant. Woad is the row of plants with yellow flowers in the vegetable garden. People there also grew cabbage and broad beans. At the bottom right is a field with broad beans. Hemp grows at the bottom left. Rope was made from the stems of hemp. Due to human activities, the typical vegetation of a farming village with all kinds of weeds, including thistles, appeared around the houses.

At the top of the illustration you see a small dike, a summer dike. The area within such a dike was protected against high water in the summer. You could also move about it. The row of posts in the creek is a primitive jetty. Perhaps they also hung fish traps on them.

back to The mound landscape

Creeks, bowers and ditches

This detail from Ulco Glimmerveen's illustration shows that the salt marshes were intersected by creeks and bowers. The sea, which you see on the horizon of this illustration, was able to flow into the salt marsh landscape through those creeks and bowers. That seems like a disadvantage, but the water brought in new, fertile clay. During storms, the water did not remain within these creeks, but flowed over the entire salt marsh. This kept the fields and grasslands fertile. They did not need to be fertilized. Field farming on undyed salt marshes appears to be possible without any problems.

The creeks were navigable. A freighter sails in the creek. It is a flat-bottomed boat that could also sail in very shallow water. Ditches were dug to drain the salt marsh, but also to divide the land and create boundaries: up to that ditch the land is mine, behind it lies your land. The ditches were connected to the natural creeks. Nature and culture were strongly intertwined. When the creeks were frozen over in winter, people could move around on skates. For this purpose, people used glissen: leg skates, made from cow and horse bones.

The salt marsh also contained common land plants such as dandelions and daisies, but no trees. Trees could not survive flooding with salt water. Large parts of the salt marshes were grasslands, with many types of grasses and all kinds of flower plants. Part of the grassland was used as hayfield. At the bottom right you can see mowed grass that was left to dry on riders. When it was dry, the farmers had hay for the winter. The house on the left of the illustration was probably a stable. It may have been used at high tide to keep livestock dry.

The lower parts of the salt marshes are depicted in the rear portion of this illustration. Salt plants such as samphire and sea lavender grew here (the purple plains). Most sheep also grazed here. Sheep can tolerate salt water well. That is why they often grazed lower on the salt marsh than cows. You can see the cows grazing on the higher parts of the salt marsh.

back to The mound landscape

Terp village with church

Op dit detail van de illustratie van Ulco Glimmerveen zie je een terpdorpje dat uit slechts twee boerderijen beslaat. In front of the house on the right is a field of hemp, in front of the house on the left is a field of barley. The mounds were connected with causeways. Bridges led over the creeks.

This village has something special, namely a mission church. It is the building in the middle, with higher walls than the farms, windows in the walls and a cross on the roof. From the 8th ecentury, the mound area gradually became christianized. This was done by missionaries from what is now Great Britain. This was a difficult process. In the 9th century, there were several of these small mission churches scattered throughout the Frisian and Groningen terpen area. The followers of the new faith buried their dead near such a church.

At the bottom center of this illustration there is a snap net next to the creek to catch birds. There are some seagulls flying around. However, the terp inhabitants ate mainly ducks, geese, swans, cranes and wading birds such as curlews, godwits, ruffs, golden plovers, redshanks and sandpipers.

back to The mound landscape

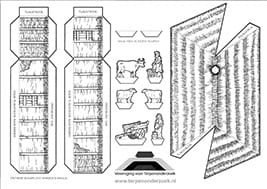

Early medieval mound village of Fé Pelsmaeker

Terpdorp in the early Middle Ages (if you click on the image, you will get a larger version; with the right button of your mouse you can save it on your laptop or PC and then include it in your paper (see the bottom of the text block))

This is a colorful reconstruction drawing of a mound in the early Middle Ages (500 to 1000 AD). It was made by artist Fé Pelsmaeker. The drawing provides a detailed picture of daily life on the mound and a beautiful overview of the salt marsh landscape. The drawing shows the salt marsh landscape and part of this landscape are the terp villages, arable farming and horticulture, livestock farming and shipping. There weren't any then sea defense dikes. The sea could come close to the farms via the creeks and bowers. The farms were located on artificial residential hills. In Friesland these are called terps, in Groningen they are called mounds.

The entire salt marsh landscape around the mounds was used by people: as a place of residence, as a field, as pasture, and as a hay field, but of course not as intensively as the agricultural landscape now. You can call it an agricultural salt marsh landscape. In the 9th century there were also simple churches here and there. At greater distances from the mounds, the influence of humans was less visible. There were still many wild animals that people also caught to eat: molluscs, fish and seals in the creeks and bowers, birds on the salt marshes and on the mudflats, the occasional red deer, a moose, a roe deer. , a wild boar.

The mounds were constructed on parts of the salt marsh that were slightly higher, the so-called salt marsh walls. The village mounds are often in a row and not randomly distributed across the salt marsh. The salt marshes continued to grow throughout the terpen period. When enough new salt marsh had formed, people started on a new row of mounds. This often started with a single house on its own mound, a house stage. In the background you can see three villages.

The terp inhabitants grew various crops in their fields. Barley was by far the most important grain of the terpen area. The residents probably cooked a kind of knitting from this. It was not used as animal feed. Other crops included flax, hemp and emmer wheat. There are also a few small fields of broad beans and a woman is busy picking them.

We see a relatively small terp village with a few farms. Some residential buildings were large, up to 30 meters long; others were shorter. The houses had no windows. There were also barns for additional stable and storage space. The farm itself also had room for livestock: cattle, sheep, horses and a few pigs. Because people and livestock lived under the same roof, these farms were called stable houses. In the drawing, a new house is just being built. The walls are made of stacked salt marsh sod, which was placed on the salt marsh. At the bottom right of the drawing you see an ox cart arriving loaded with sod and thatch for the new house.

An arch-shaped roof construction was made with wood, which was valuable in the terpen area. Wood was often used from discarded or stranded ships. Then the roof was covered with sod, grasses or straw. At the Yeb Hettinga Museum in Firdgum (Fr.) there is a replica sod house from about 700 AD. You can also view this from the inside.

Cooking and heating was mainly done with dried manure. In the middle of the mound village you see a well, where rainwater was collected. When the salt marsh was flooded with salt water, the cattle could drink here. Fresh water is especially important for dairy cows. The drinking water for the people also came from wells. Rainwater collected under the mounds, which could be reached via a well. The well has a well gallows, a construction for lowering a bucket into the well and raising it again filled with water.

A flock of sheep with their shepherd and dog is just returning to the mound. The sheep in this drawing are colored white and the cattle that roam freely are light brown. But we don't actually know what color the cattle were. Many cattle bones are recovered. But you cannot tell the color of the coat from that. A flock of chickens roams through the village led by a rooster. Two pigs are having fun in their mud puddle. There is merchandise under a shelter, mainly earthenware pots, and we see a terp resident busy at a fire. The terp inhabitants made earthenware pots themselves, but also imported them from, among others, Walberberg, Badorf and Mayen, all in modern-day Germany (information Angelique Kaspers MA, GIA/RUG).

There is a sheepskin hanging to dry. The people wore woolen or linen clothes, in beautiful colors, as you can see from the rags hanging on the line to dry at the back house. These have just been dyed with the blue dye that is extracted from the woad plant.

The wool came from our own sheep. The linen came from home-grown flax. Many spinning stones (made of pottery, bone and antler) and weaving weights (made of pottery) are found in mounds. The wool and flax were spun and woven themselves. There is a loom against one of the houses. Wool was also sold as a commodity. Frisian cloth was known far and wide. Arable farming produced more than enough products for the country's own needs. Yet the impression is that mainly livestock products, such as hides, wool and perhaps cheese, were traded.

There is a small boat in the creek next to the village, which was used for fishing, delivering or picking up goods in the area, and making visits. There were also larger boats, with a sail, that were used to bridge greater distances. The terpen area was part of trade networks throughout the North Sea region and far beyond.

The salt marsh landscape was intersected with creeks and bowers. A net is hanging to dry near the creek. The sea, which you see on the horizon of this drawing, could flow into the salt marsh landscape via those creeks and bowers. That seems like a disadvantage, but the water brought in new, fertile clay. During storms, the water did not remain within these creeks, but flowed over the entire salt marsh. This way the fields and grasslands remained fertile. They did not need to be fertilized. Field farming on undyed salt marshes appears to be possible without any problems.

The creeks were navigable. Ditches were dug to drain the salt marsh, but also to divide the land and create boundaries: up to that ditch the land is mine, behind it lies your land. The ditches were connected to the natural creeks. Nature and culture were strongly intertwined. When the creeks were frozen over in winter, people could move around on skates. For this purpose, people used glissen: leg skates, made from cow and horse bones.

The salt marsh also contained common land plants such as dandelions and daisies, but no trees. Trees could not survive flooding with salt water. Large parts of the salt marshes were grasslands, with many types of grasses and all kinds of flower plants. Part of the grassland was used as hayfield. Behind the right house you will see a haystack. When it was dry, the farmers had hay for the winter. What is that little man doing at the haystack? Of course, they didn't have toilets as we know them today.

The lower parts of the salt marshes and the tidal flats are depicted in the rear part of the drawing. Salt plants such as samphire and sea lavender grew here (the light purple plains). Most sheep also grazed here. Sheep can tolerate salt water well. That is why they often grazed lower on the salt marsh than cows. The cows grazed on the higher parts of the salt marsh. Slightly to the right of the center of the drawing you see two children playing with knuckles, which are small bones from the hind legs of sheep. The game is closely watched by the cat.

Using the drawing

Are you a student or are you working on an assignment about mounds? Then you may use this drawing, stating the source: illustrator Fé Pelsmaeker, commissioned by the Association for Terpen Research, downloaded from https://www.terpenonderzoek.nl/onderwijs/. If you would like to use the illustration in printed matter or other publications, please contact the board of the Association for Terpen Research.. The copyright rests with the Association for Terp Research.